Nam June Paik Art Center is pleased to present a special exhibition . In celebration of the 80th anniversary of the birth of Nam June Paik who led an exceptional life exploiting “boundary regions between and across various existing sciences,” this exhibition shies away from a conventional retrospective and instead sheds new light on Paik, the artist and thinker, with a thematic focus on cybernetics.

Theory of systems and information in a narrow sense, and philosophy of life and knowledge connecting man, machine and nature in a wider sense, cybernetics was a great source of inspiration for Paik who created a body of enthralling work by merging art and technology and rendered it in his vision and insight for the future.

“Nostalgia is An Extended Feedback” is borrowed from the phrase that Paik himself used as a title for his essay written in 1992 and also for one of his artworks, which, alluding to the key concept of cybernetics, i.e., feedback, is intended to emphasize the importance of looking back upon the past. This exhibition aims to enable the nostalgia for Paik felt today amplify the feedback from yesterday so that it will give rise to feedforward for tomorrow.

Replete with nostalgia for Paik, this exhibition offers a selective overview of his cybernetic constellation. TV Garden, the iconic piece of the Nam June Paik Art Center, will be combined with One Candle, to become an arena of exploring his networked ecological thinking. Marco Polo, The Rehabilitation of Genghis Kan, and many more historical and contemporary figures in the form of Paik’s robot sculptures will be theatrically staged. What will also be highlighted are the cybernetic issues of spatio-temporal multiplication, noise-information dynamics, and man-machine interactivity, in such works as Swiss Clock, Zen for Film, Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer, Three Camera Participation, and some of the arresting videos and films that Paik produced. In addition, a separate section will offer a rare chance to discover Paik’s drawings, documents and photographs through archival displays and tablet computers.

“Cybernated art is very important, but art for cybernated life is more important, and the latter need not be cybernated.” This is from the often quoted of Paik’s short manifesto. The ways Paik’s work resonates with a world of cyborg and cyberspace are brought into bold relief by the works of present-day media artists. Among others are Mary Bauermeister’s Secret Signs, Lutz Dammbeck’s The Net: The Unabomber, LSD and the Internet, Olafur Eliasson’s Your Uncertain Shadow, Catherine Ikam and Louis Fléri’s Fragments of an Archetype, Antoni Muntadas’s The File Room, and Bill Viola’s Ancient of Days. These artists are joined by Peter Campus, Valie Export, Dan Graham, Shinil Kim, and Lee Bul, whose work will all enrich the exhibition in terms of raising a question as to changing perceptions of realities in the technology-driven culture.

Paik’s statement about cybernated art and life ends with “We are in open circuits.” Nam June Paik Art Center this year takes upon itself the task of ‘open circuits,’ into which different voices can be fed and diverse feedbacks can be generated. To achieve this, a whole series of various events alongside the exhibition are organized too.

Opening performances will take place featuring Fluxus artist Takehisa Kosugi and Gayageum musician Byungki Hwang. There will be a screening program of Paik’s major videos on a huge media façade in Seoul every mid-summer night. Special lecture series runs throughout the year, whose speakers are primarily long-time collaborators with Paik, such as Wulf Herzogenrath, former director of Kunsthalle Bremen, and technicians Jochen Saueracker and Jungsung Lee. What is also not to be lost is a range of education programs, and an annual symposium is definitely part of the commemorative schedule.

For this special year, the interior of Nam June Paik Art Center is refurbished as well. The renovated “house where Nam June Paik lives on,” as Paik himself dubbed the Nam June Paik Art Center, will welcome visitors with ‘his’ open arms where Paik’s quest for open circuits is set in motion.

Nam June Paik, Marco Polo, 1993

<The Rehabilitation of Genghis-Khan> and <Marco Polo> are the robots featured in Paik’s exhibition <Artist as Nomad: Electronic Superhighway – from Venice to Ulan Bator> at the German Pavilion of the 1993 Venice Biennale. <The Rehabilitation of Genghis-Khan> is on a bicycle, the back of which is loaded with machines for information transportation, and <Marco Polo> is riding a car filled with real flowers. At the Pavilion’s garden Paik set up the ‘Scythian Road,’ analogous to the Silk Road, where he positioned cross-cultural nomads connecting the East and the West in history, represented in his robot sculptures. This was to highlight the potentiality of cultural exchanges between different societies.

Catherine Ikam and Louis Fléri, Fragments of an Archetype, 1980/2012

This work is an electronic version of Leonardo da Vinci’s <Vitruvian Man> where the Renaissance artist expressed the principles of order and harmony of the cosmos in the human body’s mathematical proportions. Calling attention to anthropocentrism, Ikam and Fléri fragmented the human body into sixteen parts to be represented in moving images, whose monitors are reassembled into a huge multi-television sculpture. To superimpose humans, screens and the globe over one another via technology could reveal the possibility of spatiotemporally distributed existence of human beings in the man-machine-nature relational network. This is none other than Paik’s cybernetic art in that Paik defines cybernetics as a science of relations, or relationship itself.

Olafur Eliasson, Your Uncertain Shadow(Growing), 2012

This work invites the audience to find his image divided into numerous ones. Using scientific methods and technology, Eliasson sublimates the elements of natural phenomena such as light, water and fog into artworks. By representing the simulated nature of his own construction in a specific space, he gives his audience a unique experience-the encounter of civilization and nature. In Eliasson’s works, the audience participation functions as an important motif. He shares common artistic goals with Paik as he strives toward the combination of nature and science, the interaction between artwork and audience, and the communication between art and society.

Antoni Muntadas, The File Room, 1994/2012

The File Room deals with ‘censorship’ in relation to authoritarian power in communication. This is a database of censorship cases in the fields of art and culture, from the ancient to the modern periods from all over the world. It has an open structure to which anyone could add a censorship case, and the still expanding database is maintained in cooperation with such organizations as National Coalition Against Censorship in the USA. The virtual database on the Internet is also transposed into a physical cell formed by piling up dozens of file cabinets. With the dark, closed and somewhat oppressive atmosphere, the viewer is invited to search the computer database and to contemplate the current meanings of two-way communication that Paik pursued.

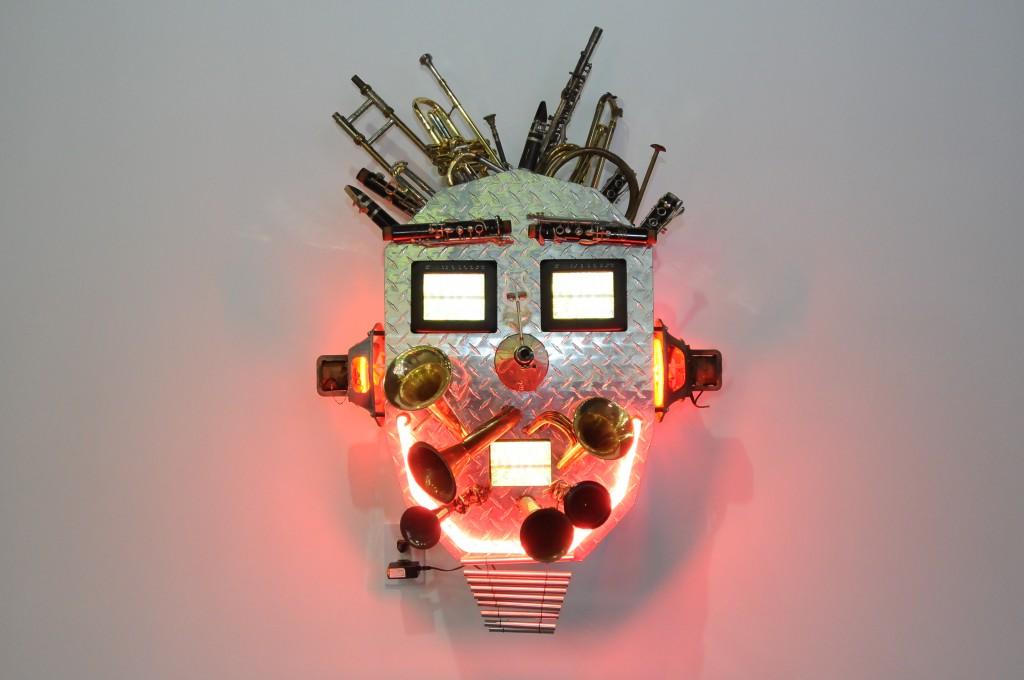

Nam June Paik, Robot Series

Nam June Paik’s interest in robots continued through the mid 1980s, resulting in the robot series called video sculpture. These robots were not controlled by men like <Robot K-456>. Instead, the old fashioned television sets substituted human bodies, and TV monitors showed the videos. Paik revived in these robots diverse historical characters such as Hippocrates, Descartes, Schubert, and Danton. He also revived the actor and film director Charlie Chaplin and the comedian Bob Hope. Furthermore, he made robots of historical Korean people such as Queen Seondeok and Yule Gok. Nam June Paik’s robots reveal their identities in their names, and their bodies constituted of various forms of televisions express human characteristics.

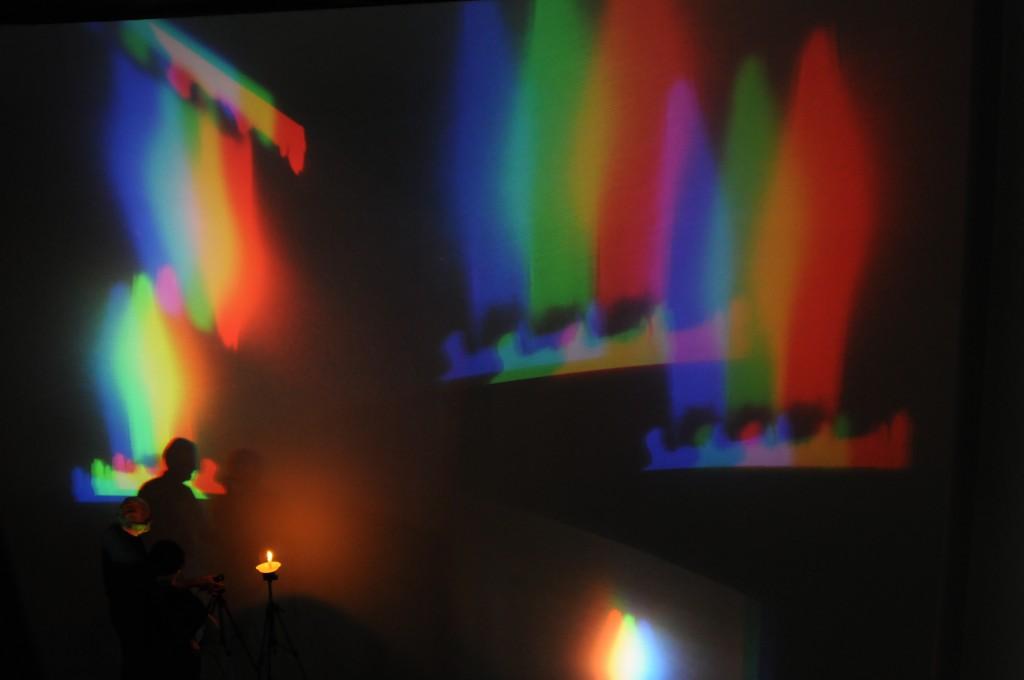

Nam June Paik, One Candle, 1989

A video camera records a live image of a burning candle on a tripod, which is reproduced by projectors on the wall. The camera has three charge-coupled devices(CCD), detecting red, green and blue light each, and the old-fashioned projector also has three cathode-ray-tubes. Paik used these machines, which are supposed to create an image by converging separate rays of light into a single projection, in the way that deconstructs the image. Instead of merging the candle’s images separated by color inside the machines, Paik chose to project the separate images as layers directly onto the wall. The projected images formed by combinations of the layers on the wall are thus in various composites of color, size and shape. The candle’s image subtly waves since the flame is moved by the flow of air and the viewer’s movement around; it also keeps changing because the candle is being burnt away in the course of time. With equipments and cables deliberately exposed on the floor, in contrast with the swaying images on the wall, viewers can observe the whole space as a kind of closed circuit.

Nam June Paik, Happy Hoppi, 1995

The title “Happy Hoppi” is composed by putting an adjective ‘happy’ before the name of a Native American tribe ‘Hopi’ – Paik seems to have added one more ‘p’ to ‘Hopi’ for a visual likeness to ‘happy’ – so that the two words rhyme with each other. The work presents a figure of the Native American made of twenty monitors, with his head and hands decorated by neon tubes and light bulbs as if wearing a headdress and holding a bow and arrow in both hands. On the screens, a robotic human being strolls in the space that looks like a 3D diagram, and what is also floating in graphic forms are cars, airplanes, satellites, telephones, computers and optical discs. The Hopi figure sits on a scooter whose front is painted like a shield or a mask. In Hopi mythology there were a god of sky on a flying shield and a messenger spirit connecting different worlds, who are often represented in masks. Combining the modern icons of transportation and communication, Paik borrows the cultural subjects of Native Americans who used to be ‘others’ in the Western-centric narratives of human history, thereby raising a question on the meanings of being truly global.

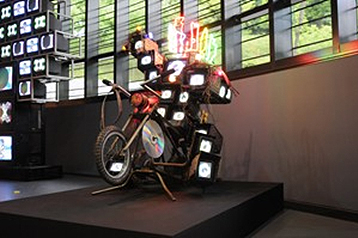

Nam June Paik, Easy Rider, 1995

Easy Rider shares its title with a movie directed by Dennis Hopper where two rebellious young men ride motorcycles across the United States in search of an alternative way of life. Released in 1969, the controversial movie depicted the young people of the time that denied the existing social system, became members of the hippie movement and used psychedelic drugs. Nam June Paik wrote in his 1974 essay titled “Media Planning for the Postindustrial Society – The 21st Century is now only 26 years away” that the history of the 1960s witnesses the fact that the problem of communication that is the gap between generations can awaken the society and its value system. Easy Rider suggests a way of communication towards a new society through a broadband communication of an electronic highway. With a body that is consisted of 16 television monitors, a robot is riding on a motorcycle. On its body, license plates are attached as if they were medals that imply its journey. A dazzling decoration made of neon lights is attached to its head, bulbs with various colors on its arms. Laserdisc decorations with their rainbow of hues remind of the free and wild protagonists of the movie.