Going on the Maiden Voyage

Wisdom which drives itself away is by no means wise. Sense of humor stems from the ability to encompass the whole in one view. Play and sense of humor are the spirit of art.

Nam June Paik wanted to use his video camera to record Marcel Duchamp and John Cage playing chess. Duchamp’s premature death frustrated Paik’s plan. However, Shigeko Kubota’s series of photographs still remain. ‘Going beyond Duchamp’ was a predominant slogan in Western art for a considerable period of time, yet it did not arouse much interest in the non-Western world, or when it did, it was as an intellectual curiosity. Thus, the process of detecting, exaggerating and even disseminating the supposed clues in Duchamp’s ways of thinking has only been possible and meaningful in the Western-centered system of art. When the politics of difference challenge the hierarchy of quality and increasingly threaten Western-dominated codes as they seep from the cultural battlefield of Europe and the U.S. to the rest of the world, Nam June Paik needs to be summoned.

In one of his interviews, Paik said: “Marcel Duchamp has already done everything there is to do – except video. He widened the entry but narrowed the exit. That very narrow door is video art and only through video art can we go beyond Marcel Duchamp.”

The image of Paik as a possible way out from Duchamp’s shadow evokes ‘Poor Old Hamilton’ by Chinese artist, Wang Xing Wei, one of the first works to be encountered by the Now Jump audience. In this painting a naughty child (dressed in a Chinese army uniform) ignorant of the weight of contemporary art inadvertently breaks Duchamp’s Large Glass. It is possible to imagine that this cheeky little boy is none other than the pampered, innocent-looking child that comes to life in Paik’s art.

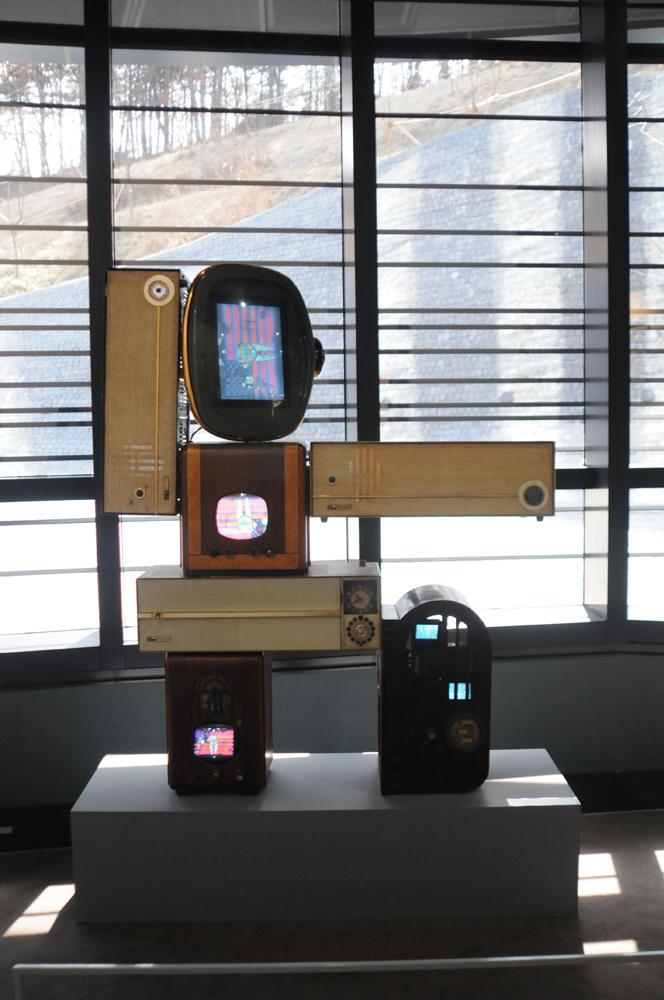

Paik’s liberal and broad-minded spirit motivated him to hang a cow’s head on the door of the gallery in his first exhibition. This act was suggestive of ritual behavior and highly saturated with a self-reflexive anarchism directed at severing the head of power. Unaware of the nightmare of Auschwitz and the historical guilt inscribed into the subconscious of post-war Germany (and Europe), Paik was able to engage with media, from TV and video to technology in the broadest sense, in an innovative, unrestrained and bold way that restored laughter through radical performances and sense of humor. It was by restoring this gratifying laughter to the generation between both World Wars, the one gripped by collective hypochondria and a sense of victimhood, that Paik was transformed into the historical a priori in the fusion of art and technology. To the public, Paik was seen as a jolly clown, always glorifying life, creation and joy.

Through his hands, TV and video, with their immense potentials as communication networks, developed from a mere vehicle used to deliver social and political messages into a combination of tele-visual graffiti and popular culture. The illusionistic state of experience that corresponds to the height of introspection can be found in the Buddhist image of the Mandala or the stained glass of medieval cathedrals. Paik’s creativity with media brings to the surface this state of experience within the public space of participation where this conciliation between different states of experience occurs. This path of experience can be echoed in the life of an artist aiming to achieve emancipation unfettered by relative ideologies and the natural human cycle of birth, aging, illness and death. This struggle for indeterminateness represents a continuous circuit of self-revolution where plugging into life is destined to achieve freedom for freedom’s sake.