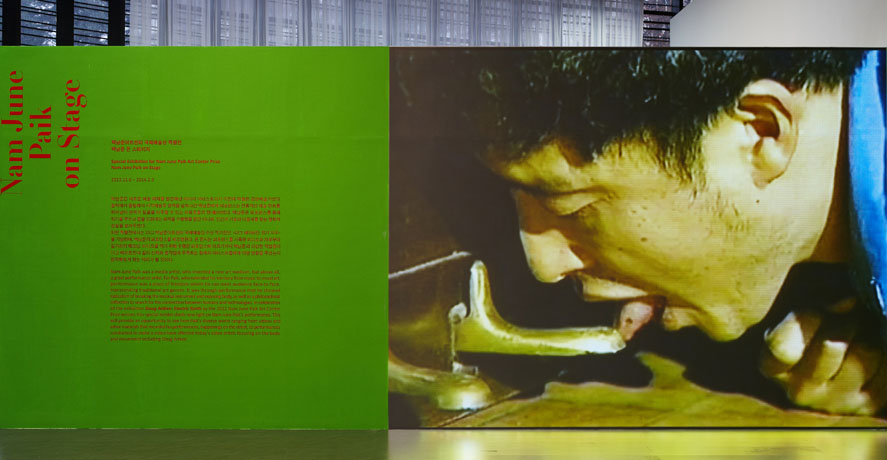

I. Catherine Ikam, Paik Plays Piano Pieces, 2012, video, color-sound, 12min 32sec

Paik’s colleague Catherine Ikam, a video installation (sculpture) artist, made a documentary from the videos containing Paik’s reenactment of his major performances in the studio. Whereas the performer’s gestures are usually hard to observe perfectly due to a number of variables and noises in the recording of live performance, her documentary displays every single gesture of Paik. Presented for the first time in Korea, this video includes the scenes of Paik’s performance in front of chroma key green screen. Accordingly, it leaves a possibility that the late Paik can exist in a work of new time and space with image synthesis techniques.

II. Paik’s Performances (selected)

Paik’s performances were different in their form every time he performed even if they were under the same title. Besides, the detailed contents of performance also differed as he mixed a variety of performances. This exhibition mainly focuses on his premieres and in case of the performance with big changes, its contents are explained.

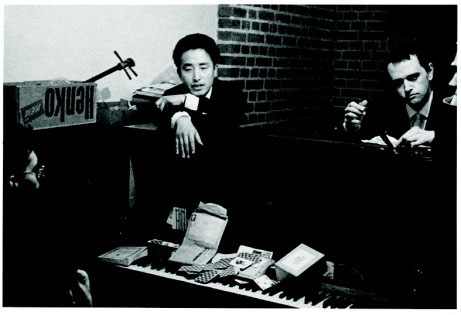

Hommage à John Cage, 1959

Paik, who found a new world of art after meeting John Cage, created a sound collage and performance dedicated to Cage. After recording and editing a range of sounds from classical music to noises of daily life in a reel tape, he played it with the so-called ‘Prepared Piano’ that he manipulated and modified. Classical music includes Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, Das Lied, and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2, while non-music sounds include screams, sound of breaking glass, that of stone in the metal box, a rooster’s crow, a lottery announcement, news reports, and sound of Prepared Piano.

Étude for Pianoforte, 1960

In the performance of

<Étude for Pianoforte>

held in his fellow artist Mary Baumeister’s studio, Paik stops playing Chopin, runs around crying, and breaks down the piano. Then he runs into John cage sitting in the audience and cuts off his shirt and tie. He shampoos over the hair of John Cage and David Tudor and then runs out somewhere. After a moment, he calls and says that performance is finished, and on the stage, there is a motorcycle left with its engine on, without a rider.

Simple, 1961

Paik quietly walked up to the stage and threw the beans at the audience and the ceiling. Then he shed tears while covering and uncovering his face slowly with paper and wet it with tears. A woman’s shout, radio news, children’s noise, classical music, electronic sounds played for about 15 seconds, when he suddenly shouted, threw the paper, and played the tape recorder. He applied his shaving cream from his face to his clothes and to toe, poured flour on him and ran into the bathtub. He finally approached the piano and played it with his head.

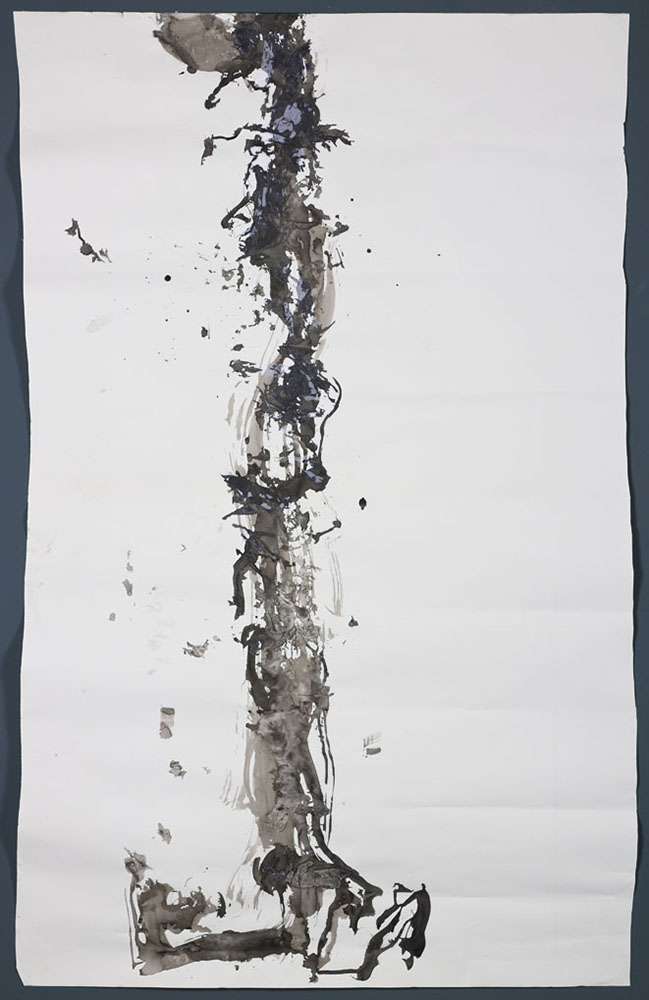

Zen for Head, 1961

Nam June Paik performed for the first time in the performance of the piece (It means “originals” in German) by Karlheinz Stockhausen. He dips his hair in ink like a brush and slowly draws a line on paper placed on the floor. In this way, he even left the traces of subtle movements of the body. This is the first piece of his “Zen” series, of which the content of radical actions presents a striking contrast with quiet gestures.

One for Violin Solo, 1962

In this performance, Paik slowly lifts up a violin and then smashes it at a stroke. The score says, “Lift up a violin over the course of 5 minutes.” It is often interpreted as an action to bid farewell to conventional classical music, and a violinist from the Dusseldorf Symphony Orchestra actually shouted, “Save that violin!” in the middle of the performance. Watching this performance, a representative work of his early performances, audiences are devastated by the obvious contrast between the stifling action of lifting a violin very slowly and the unexpected action of smashing it at one blow.

Serenade for Alison, 1962

Alison Knowles, who was called “a beautiful paintress” by Paik, stood up on the table wearing a bathrobe made of multicolored fabric, typical of Korean traditional costume (Hanbok) in a gallery in Amsterdam. Knowles, surrounded by male audiences including Paik, took off pair after pair of nine panties like a stripper. Paik’s original score says, “Look at the audience through the panties,” “Pull them over the head of a snob,” “Take off a pair of blood-stained panties, and stuff them in the mouth of the worst music critic,” and in the end, “If possible, show them that you have no more panties on.” But Knowles did not follow the score as it was, and instead modified it; she threw each pair of panties to the audience with radios on her neck and led them out of the gallery.

Robot Opera, 1964

Presented first in “The 2nd New York Avant-Garde Festival” established by Cellist Charlotte Moorman, this work features a remote controlled robot that walks around and Moorman who plays cello. , a fragile and flimsy robot, plays a recording of John F. Kennedy’s speech, defecates beans, and its chest swells as if it is breathing, while barely managing to walk on the street under Paik’s control. In his retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (1982), he staged a situation in which this robot had a car accident, and he declared its death in the end of the performance by referring to it as “the first catastrophe of the 21st century.”

26’1.1499” for a String Player by John Cage, 1965

This work is a reinterpretation of the score composed by John Cage in 1955 by Nam June Paik in collaboration with Charlotte Moorman. The premiere of this piece is known for the scene that Moorman plays the strings installed on the back of topless Paik as if it is a cello. Cage’s original version is an experiment of sound in which a performer is supposed to play cello while making sound of a few materials one by one. Paik and Moorman made sounds utilizing a wider range of materials, and extended these sounds into the social issues. In the performance held in 1973, Moorman shot a starter gun, tapped a glass bottle, popped a balloon with teeth, and drank coke and burped. Then she hugged a bomb instead of the cello, scratched it with her hands and a saw, read a text or screamed, and finally called the White House and asked for the President.

Opéra Sextronique, 1966

This performance work features Charlotte Moorman, who plays the cello whilst taking off her clothes. It was premiered in Aachen, Germany in 1966, but caused a huge sensation in its New York presentation in 1967 because of the arrest of Moorman by the police. Eventually, it served to revise the law on performances in New York State.

*For more information, please refer to the works and materials displayed in the exhibition <> on the first floor.

TV Bra for Living Sculpture, 1969

is an artwork consisting of two miniature televisions put in the two plexiglass boxes to be attached to the upper body with a set of vinyl straps. It is also the title of performance in which the performer plays the cello wearing this piece. TV monitors display television programs on the air, feed of closed-circuit video cameras, or recorded videos. At times, recorded sound of cello becomes a noise in the video. As he put it, “TV Bra for Living Sculpture is also one sharp example to humanize electronics… and technology.”

Concerto for TV Cello and Videotapes, 1971

This work presents a performance of playing the consisting of a few different-sized TV sets connected by the strings on top of them to form a shape of a cello. It is mainly composed of 3-channel videos: a local TV program of the area where the performance takes place, recorded video or synthesized images, and a real time feed from closed-circuit cameras recording the performance. With the sound of Moorman’s musical performance added, this concerto covers various mechanisms of electronic art such as communication, recording, editing, interaction as well as improvisation.

III. Paik’s Street Happenings

Paik entered a space of everyday life or embraced unexpected situations into his works by means of performances close to the happenings on the street in addition to those on the stage. Different from his concentrated and charismatic appearance on the stage, Nam June Paik on the street approached the public in a more relaxed and cheerful way. The performance of the Korean traditional exorcism “Gut” carried out in the 1994 at the Washington Square Park, and the happening in which he broke the violin at the Harvard Square show his sense of humor and composure in his later years.

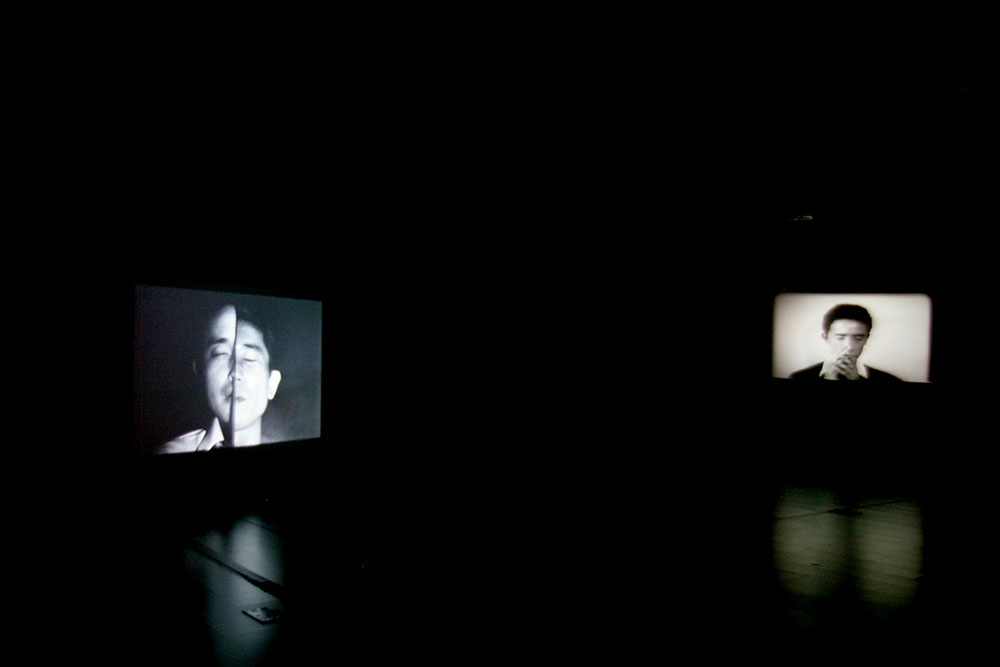

IV. Performance-Video

Even if Paik recorded the scenes of his performances and utilized them as materials for his video works plenty of times, he occasionally conducted a performance to make a video. For the monochrome videos (1965) and (1967-1972), which are on display in the “Memorabilia” space, a replica of Paik’s New York studio, he performed in front of the camera personally in order to make a video. These works suggest a close relationship between performance and video art, and at the same time, raise a question of how to distinguish documentaries of performance from video art.